Planet Python

Last update: March 14, 2026 04:43 AM UTC

March 13, 2026

EuroPython

Humans of EuroPython: Kshitijaa Jaglan

Discover the motivations behind volunteering, the challenges and rewards of organizing such a significant conference, and the impact it has on both attendees and contributors. Hear personal stories and learn how individuals like our interviewee help shape the future of Python through their commitment and collaboration.

In our latest interview Kshitijaa Jaglan, a member of the Sponsorship Team at EuroPython 2025, shares thoughts on enabling sponsors, finding a new community, and more.

Kshitijaa Jaglan, a member of the Sponsorship Team at EuroPython 2025

Kshitijaa Jaglan, a member of the Sponsorship Team at EuroPython 2025EP: Had you attended EuroPython before volunteering, or was volunteering your first experience with it?

I attended EuroPython remotely during COVID, but this was my first time at the conference in person, and my first time volunteering!

EP: What&aposs one task you handled that attendees might not realize happens behind the scenes at EuroPython?

I worked in the sponsorship team, and it’s not as attendee-facing as some other teams. A big part is building and maintaining relationships. For the new sponsors, we’re the face of the conference, and everything we do reflects on it. For the returning ones who chose to trust us again, it is our responsibility to maintain that level of credibility and ensure a fruitful experience for everyone involved!

EP: How did volunteering for EuroPython impact your relationships within the community?

Before volunteering, I barely knew anyone beyond a few names on LinkedIn and Twitter. When I showed up on crutches on day one, I wasn&apost sure what to expect, but the warmth was immediate. I still remember meeting Anežka on day one and her energy felt like we&aposd known each other forever. Now, ramping up for EuroPython 2026 and seeing everyone&aposs faces on gMeet brings back all the joy. I came in knowing no one, now this community feels like home.

EP: What&aposs one thing you took away from the experience that you still use today?

How genuinely people in this community root for each other. You see it in small moments, like Raquel cheering me on from her A/V setup while I was on stage. That kind of support sticks with you and reminds you to show up the same way for others.

EP: If you could add one thing to make the volunteer experience even better, what would it be?

I wish the conference lasted for a few more days!

EP: Do you have any tips for first-time EuroPython volunteers?

EuroPython is a welcoming community - you’ll bond over shared experiences before you know it! Just stay open, and your environment will do the rest.

EP: If you could describe the volunteer experience in three words, what would they be?

Wholesome beautiful chaos.

EP: Thank you for your contribution to the conference, Kshitijaa!

Talk Python to Me

#540: Modern Python monorepo with uv and prek

Monorepos -- you've heard the talks, you've read the blog posts, maybe you've seen a few tantalizing glimpses into how Google or Meta organize their massive codebases. But it's often in the abstract and behind closed doors. What if you could crack open a real, production monorepo, one with over a million lines of Python and over 100 of sub-packages, and actually see how it's built, step by step, using modern tools and standards? That's exactly what Apache Airflow gives us. <br/> <br/> On this episode, I sit down with Jarek Potiuk and Amogh Desai, two of Airflow's top contributors, to go inside one of the largest open-source Python monorepos in the world and learn how they manage it with uv, pyproject.toml, and the latest packaging standards, so you can apply those same patterns to your own projects.<br/> <br/> <strong>Episode sponsors</strong><br/> <br/> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/agentic-ai'>Agentic AI Course</a><br> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/devopsbook'>Python in Production</a><br> <a href='https://talkpython.fm/training'>Talk Python Courses</a><br/> <br/> <h2 class="links-heading mb-4">Links from the show</h2> <div><strong>Guests</strong><br/> <strong>Amogh Desai</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/amoghrajesh?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <strong>Jarek's GitHub</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/potiuk?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <br/> <strong>definition of a monorepo</strong>: <a href="https://monorepo.tools?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >monorepo.tools</a><br/> <strong>airflow</strong>: <a href="https://airflow.apache.org?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >airflow.apache.org</a><br/> <strong>Activity</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/apache/airflow/pulse?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <strong>OpenAI</strong>: <a href="https://airflowsummit.org/sessions/2025/airflow-openai/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >airflowsummit.org</a><br/> <strong>Part 1. Pains of big modular Python projects</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-1-1fe84863e1e1?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 2. Modern Python packaging standards and tools for monorepos</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-2-9b53e21bcefc?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 3. Monorepo on steroids - modular prek hooks</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-3-77373d7c45a6?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>Part 4. Shared “static” libraries in Airflow monorepo</strong>: <a href="https://medium.com/apache-airflow/modern-python-monorepo-for-apache-airflow-part-4-c9d9393a696a?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >medium.com</a><br/> <strong>PEP-440</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0440/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-517</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0517/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-518</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0518/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-566</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0566/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-561</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0561/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-660</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0660/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-621</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0621/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-685</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0685/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-723</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0732/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>PEP-735</strong>: <a href="https://peps.python.org/pep-0735/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >peps.python.org</a><br/> <strong>uv</strong>: <a href="https://docs.astral.sh/uv/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >docs.astral.sh</a><br/> <strong>uv workspaces</strong>: <a href="https://blobs.talkpython.fm/airflow-workspaces.png?cache_id=294f57" target="_blank" >blobs.talkpython.fm</a><br/> <strong>prek.j178.dev</strong>: <a href="https://prek.j178.dev?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >prek.j178.dev</a><br/> <strong>your presentation at FOSDEM26</strong>: <a href="https://fosdem.org/2026/schedule/event/WE7NHM-modern-python-monorepo-apache-airflow/?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >fosdem.org</a><br/> <strong>Tallyman</strong>: <a href="https://github.com/mikeckennedy/tallyman?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >github.com</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Watch this episode on YouTube</strong>: <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SKd78ImNgEo" target="_blank" >youtube.com</a><br/> <strong>Episode #540 deep-dive</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/episodes/show/540/modern-python-monorepo-with-uv-and-prek#takeaways-anchor" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm/540</a><br/> <strong>Episode transcripts</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/episodes/transcript/540/modern-python-monorepo-with-uv-and-prek" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Theme Song: Developer Rap</strong><br/> <strong>🥁 Served in a Flask 🎸</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/flasksong" target="_blank" >talkpython.fm/flasksong</a><br/> <br/> <strong>---== Don't be a stranger ==---</strong><br/> <strong>YouTube</strong>: <a href="https://talkpython.fm/youtube" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-youtube"></i> youtube.com/@talkpython</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Bluesky</strong>: <a href="https://bsky.app/profile/talkpython.fm" target="_blank" >@talkpython.fm</a><br/> <strong>Mastodon</strong>: <a href="https://fosstodon.org/web/@talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-mastodon"></i> @talkpython@fosstodon.org</a><br/> <strong>X.com</strong>: <a href="https://x.com/talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-twitter"></i> @talkpython</a><br/> <br/> <strong>Michael on Bluesky</strong>: <a href="https://bsky.app/profile/mkennedy.codes?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" >@mkennedy.codes</a><br/> <strong>Michael on Mastodon</strong>: <a href="https://fosstodon.org/web/@mkennedy" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-mastodon"></i> @mkennedy@fosstodon.org</a><br/> <strong>Michael on X.com</strong>: <a href="https://x.com/mkennedy?featured_on=talkpython" target="_blank" ><i class="fa-brands fa-twitter"></i> @mkennedy</a><br/></div>

PyCharm

Last week marked the fruition of almost a year of hard work by the entire PyCharm team. On March 4th, 2026, we hosted Python Unplugged on PyTV, our first-ever community conference featuring a 90s music-inspired online conference for the Python community.

Python Unplugged on PyTV – Free Online Python ConferenceThe PyCharm team is a fixture at Python conferences globally, such as PyCon US and EuroPython, but we recognize that while attending a conference can be life-changing, the costs involved put it out of reach for many Pythonistas.

We wanted to recreate the entire Python conference experience in a digital format, complete with live talks, hallway tracks, and Q&A sessions, so anyone, anywhere in the world, could join in and participate.

And we did it! Superstar speakers from across the Python community joined us in our studio in Amsterdam, Netherlands – the country where Python was born. Some of them traveled for over 10 hours, and one even joined with their newborn baby! Travis Oliphant, of Numpy and Scipy fame, was ultimately unable to join us in person, but he kindly pre-recorded a wonderful talk and participated in a live Q&A after it, despite it being very early morning in his time zone.

Cheuk Ting Ho, Jodie Burchell, Valerie Andrianova

Cheuk Ting Ho, Jodie Burchell, Valerie Andrianova

The PyCharm team is extremely grateful for the community’s support in making this happen.

The event

We livestreamed the entire event from 11am to 6:30pm CET/CEST, almost seven and a half hours of content, featuring 15 speakers, a PyLadies panel, and an ongoing quiz with prizes. Topics covered the future of Python, AI, data science, web development, and more.

Here is the complete list of speakers and timestamped links to their talks:

- Carol Willing – JupyterLab Core Developer

- Deb Nicholson – Executive Director, Python Software Foundation

- Ritchie Vink – Creator of Polars

- Travis Oliphant – Creator of NumPy

- Sarah Boyce – Django Fellow

- Sheena O’Connell – Python Software Foundation Board Member

- Marlene Mhangami – Senior Developer Advocate at Microsoft

- Carlton Gibson – Creator of multiple open-source projects in the Django ecosystem

- Tuana Çelik – Developer Relations Engineer at LlamaIndex

- Merve Noyan – Machine Learning Engineer at Hugging Face

- Paul Everitt – Developer Advocate at JetBrains

- Mark Smith – Head of Python Ecosystem at JetBrains

- Georgi Ker – Director and Fellow of the Python Software Foundation

- Una Galyeva – Head of AI at Geobear Global and PyLadies Amsterdam organizer

- Jessica Greene – Senior Machine Learning Engineer at Ecosia

The studio room with presenter’s desk and Q&A table.

The studio room with presenter’s desk and Q&A table.

Production meeting the day before the event

Production meeting the day before the event

We spent the afternoon doing final checks and a run-through with the studio team at Vixy Live. They were very professional and patient with us as we were working in a studio for the first time. With their help, we were confident that the event the next day would go smoothly.

Livestream day

On the day of the livestream, we arrived early to get our makeup done. The makeup artists were absolute pros, and we all looked great on camera. One of our speakers, Carol, jokingly said that she is now 20 years younger! The hosts, Jodie, Will, and Cheuk, were totally covered in ‘90s fashion and vibes.

Python Team Lead Jodie Burchell bringing the 90s back

Python Team Lead Jodie Burchell bringing the 90s back

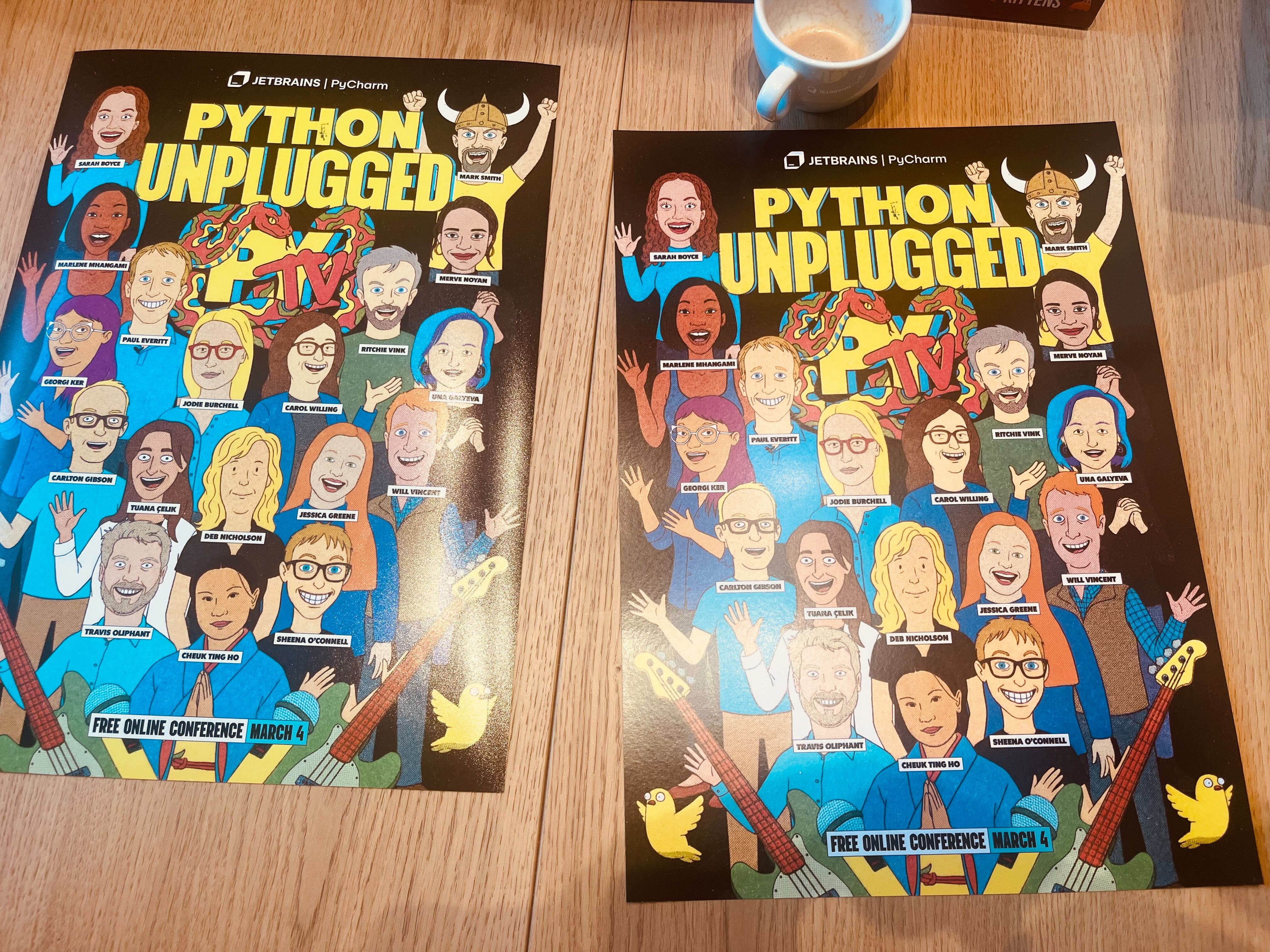

We also had swag designed by our incredible marketing team, including t-shirts, stickers, posters, and tote bags.

PyTV Stickers for all participants

PyTV Stickers for all participants

PyTV Totebags

PyTV Totebags

PyTV posters

PyTV posters

Python content for everyone

After a brief opening introducing the conference and the event Discord, we began with a series of talks focused on the community, learning Python, and other hot Python topics. We also had two panels, both absolutely inspiring: one on the role of AI in open source and another featuring prominent members of PyLadies.

Following our first block of speakers, we moved on to web development-focused talks from key people involved with the Django framework. We then had a series of talks from experts across the data science and AI world, including speakers from Microsoft, Hugging Face, and LlamaIndex, who gave us up-to-date insights into open-source AI and agent-based approaches. We ended with a talk by Carol Willing, one of the most respected figures in the Python community.

Throughout the day, we ran a quiz for the audience to test their knowledge about Python and the community. Since we had many audience members learning Python, we hope they learned some fun facts about Python through the quiz.

First of 8 questions on the Python ecosystem

First of 8 questions on the Python ecosystem

Sarah Boyce, Will Vincent, Sheena O’Connell, Carlton Gibson, Marlene Mhangami

Sarah Boyce, Will Vincent, Sheena O’Connell, Carlton Gibson, Marlene Mhangami

Next year?

Looking at the numbers, we had more than 5,500 people join us during the live stream, with most of them watching at least one talk. We’ve since had another 8,000 people as of this writing watch the event recording.

We’d love to do this event again next year. If you have suggestions for speakers, topics, swag, or anything else please leave it in the comments!

Rodrigo Girão Serrão

TIL #141 – Inspect a lazy import

Today I learned how to inspect a lazy import object in Python 3.15.

Python 3.15 comes with lazy imports and today I played with them for a minute.

I defined the following module mod.py:

print("Hey!")

def f():

return "Bye!"Then, in the REPL, I could check that lazy imports indeed work:

>>> # Python 3.15

>>> lazy import mod

>>>The fact that I didn't see a "Hey!" means that the import is, indeed, lazy. Then, I wanted to take a look at the module so I printed it, but that triggered reification (going from a lazy import to a regular module):

>>> print(mod)

Hey!

<module 'mod' from '/Users/rodrigogs/Documents/tmp/mod.py'>So, I checked the PEP that introduced explicit lazy modules and turns out as soon as you reference the lazy object directly, it gets reified.

But you can work around it by using globals:

>>> # Fresh 3.15 REPL

>>> lazy import mod

>>> globals()["mod"]

<lazy_import 'mod'>This shows the new class lazy_import that was added to support lazy imports!

Pretty cool, right?

PyCharm

Python Unplugged on PyTV Recap

Real Python

The Real Python Podcast – Episode #287: Crafting and Editing In-Depth Tutorials at Real Python

What goes into creating the tutorials you read at Real Python? What are the steps in the editorial process, and who are the people behind the scenes? This week on the show, Real Python team members Martin Breuss, Brenda Weleschuk, and Philipp Acsany join us to discuss topic curation, review stages, and quality assurance.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Quiz: Your Python Coding Environment on Windows: Setup Guide

Test your understanding of Python Coding Setup on Windows.

By working through this quiz, you’ll review the key steps for setting up a Python development environment on Windows. You’ll cover system updates, Windows Terminal, package managers, PowerShell profiles, environment variables, and safe use of remote scripts.

You’ll also check practical details like configuring Path, managing Python versions, using version control, and streamlining your workflow.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

PyPy

PyPy v7.3.21 release

PyPy v7.3.21: release of python 2.7, 3.11

The PyPy team is proud to release version 7.3.21 of PyPy after the previous release on July 4, 2025. This is a bug-fix release that also updates to Python 3.11.15.

The release includes two different interpreters:

PyPy2.7, which is an interpreter supporting the syntax and the features of Python 2.7 including the stdlib for CPython 2.7.18+ (the

+is for backported security updates)PyPy3.11, which is an interpreter supporting the syntax and the features of Python 3.11, including the stdlib for CPython 3.11.15.

The interpreters are based on much the same codebase, thus the double release. This is a micro release, all APIs are compatible with the other 7.3 releases.

We recommend updating. You can find links to download the releases here:

We would like to thank our donors for the continued support of the PyPy project. If PyPy is not quite good enough for your needs, we are available for direct consulting work. If PyPy is helping you out, we would love to hear about it and encourage submissions to our blog via a pull request to https://github.com/pypy/pypy.org

We would also like to thank our contributors and encourage new people to join the project. PyPy has many layers and we need help with all of them: bug fixes, PyPy and RPython documentation improvements, or general help with making RPython's JIT even better.

If you are a python library maintainer and use C-extensions, please consider making a HPy / CFFI / cppyy version of your library that would be performant on PyPy. In any case, cibuildwheel supports building wheels for PyPy.

What is PyPy?

PyPy is a Python interpreter, a drop-in replacement for CPython It's fast (PyPy and CPython performance comparison) due to its integrated tracing JIT compiler.

We also welcome developers of other dynamic languages to see what RPython can do for them.

We provide binary builds for:

x86 machines on most common operating systems (Linux 32/64 bits, Mac OS 64 bits, Windows 64 bits)

64-bit ARM machines running Linux (

aarch64) and macos (macos_arm64).

PyPy supports Windows 32-bit, Linux PPC64 big- and little-endian, Linux ARM 32 bit, RISC-V RV64IMAFD Linux, and s390x Linux but does not release binaries. Please reach out to us if you wish to sponsor binary releases for those platforms. Downstream packagers provide binary builds for debian, Fedora, conda, OpenBSD, FreeBSD, Gentoo, and more.

What else is new?

For more information about the 7.3.21 release, see the full changelog.

Please update, and continue to help us make pypy better.

Cheers, The PyPy Team

Daniel Roy Greenfeld

To return a value or not return a value

I believe any function that changes a variable should return a variable. For example, I argue that Python's random.shuffle() is flawed. This is how random.shuffle() unfortunately works:

import random

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(f"Original list: {my_list}")

# Change happens in place

# my_list is forever changed

random.shuffle(my_list)

print(f"Shuffled list: {my_list}")

In my opinion, random.shuffle() should work like this:

import random

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# Function returns a new, shuffled list

new_list = random.shuffle(my_list)

print(f"Original list: {my_list}")

print(f"Shuffled list: {new_list}")

Of course, Python won't fix this mistake to fit my preference. There's too many places in the universe expecting random.shuffle to change a list in place. Yet it still bugs me every time I see the function. Stuff like this is why I created my listo package, it allowed me to get past my own sense of annoyance. The listo library is barely used, even by myself, serving mostly as a fun exercise that allowed me to scratch an itch about objects changing in place.

Counterargument

Some of you might say, "It's not practical to return giant dict or list objects when you are changing a single value". You are correct. However, does it make sense for random.shuffle and other offenders to muck around with the entirety of a variable's contents? Why shouldn't a function that disrupts the entirety of a variable just return a new variable?

Closing statement

My preference is that when it is reasonable, that the scope is not outrageous, to create functions that return values.

Also, to the people who implemented the original random.shuffle function, you are awesome. I'm just taking advantage of having 20/20 hindsight.

The Python Show

56 - Python Illustrated

In this episode, we hear from two sisters who put together a beginner's book about Python. The unique hook for their book is that one sister wrote the text while the other did the illustrations. Listen in as we learn about these incredible sisters and how they got into software programming, writing, and technical education.

You can check out their book, Python Illustrated, on Packt or Amazon.

Maaike is an Udemy instructor, and she also has courses on Pluralsight.

Audrey M. Roy Greenfeld

Staticware 0.2.0: The first cut

This is an early release. Staticware does something very satisfyingly today: it serves static files with content-hashed URLs for cache busting. That means when you edit your CSS then redeploy and restart your server, visitors get the latest CSS without forcing a refresh. More will come.

I originally created the code behind Staticware as part of Air, building static file handling was built directly into the framework. Extracting it into standalone ASGI middleware meant that anyone building with Starlette, FastAPI, or raw ASGI could use it too, not just Air users. I even started a PR exploring getting it working with Django.

This package is dedicated to the memory of Michael Ryabushkin (aka goodwill), who died in 2025. Michael was a Pyramid developer who also helped host and grow the LA Django community. He believed that when you build something useful, you should build it for everyone, not just your own framework's users. He advocated that Python web developers learn to write packages generalized enough for the whole community to benefit. Staticware exists as a standalone ASGI library instead of framework-specific code because that's the kindest way to build it, and Michael was one of the people who made that obvious.

uv add staticware

What's in this release

Content-hashed static file serving. HashedStatic("static") scans a directory at startup, computes content hashes, and serves files at URLs like /static/styles.a1b2c3d4.css. Hashed URLs get Cache-Control: public, max-age=31536000, immutable. Original filenames still work with standard caching, and repeated requests return 304 Not Modified.

Automatic HTML rewriting. StaticRewriteMiddleware wraps any ASGI app and rewrites static paths in HTML responses to their hashed equivalents. Streaming responses are buffered and rewritten transparently. Non-HTML responses pass through untouched.

Template URL resolution. static.url("styles.css") returns the cache-busted URL for use in any template engine. Unknown files return the original path with the prefix, so nothing breaks if a file is missing from the directory.

Aims to work with every ASGI framework. Tested with Starlette, FastAPI, Air, and raw ASGI. I've started experimental exploration of it with Django in a PR but that's not part of this release yet. Supports root_path for mounted sub-applications so cache-busted URLs work correctly behind reverse proxies and path prefixes.

Security built in. Path traversal attempts are rejected at both startup (files resolving outside the directory are excluded) and serving time (resolved paths are validated). Files that could escape the static directory never make it into the URL map.

Contributors

@audreyfeldroy (Audrey M. Roy Greenfeld) designed and built staticware: the hashing engine, ASGI serving, HTML rewriting middleware, path traversal protection, 304 support, root_path handling, and the full test suite.

@pydanny (Daniel Roy Greenfeld) reviewed and merged the middleware return value fix (PR #2).

March 12, 2026

Python Morsels

Standard error

Standard error is one of the two writable file streams that is used for printing errors, warning messages, or any outputs that shouldn't be mixed with the main program.

Printing writes to "standard output" by default

When we call Python's print function, Python will write to standard output:

>>> print("Hi!")

Hi!

Standard output is a file-like object, also known as a file stream.

The standard output file-like object is represented by the stdout object in Python's sys module.

If we look at the documentation for Python's print function, we'll see that by default, print writes to sys.stdout:

>>> help(print)

Help on built-in function print in module builtins:

print(*args, sep=' ', end='\n', file=None, flush=False)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

sep

string inserted between values, default a space.

end

string appended after the last value, default a newline.

file

a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

flush

whether to forcibly flush the stream.

If we call the write method on sys.stdout, text will write to the terminal screen:

>>> import sys

>>> bytes_written = sys.stdout.write("Hello!\n")

Hello!

Python also has a "standard error" stream

Standard output is actually one …

Read the full article: https://www.pythonmorsels.com/standard-error/

Real Python

Quiz: Working With Files in Python

In this quiz, you’ll test your understanding of Working With Files in Python.

By working through this quiz, you’ll revisit key techniques for handling files and directories in Python. You’ll practice safely opening files, iterating over directories, and filtering entries to select only files or subdirectories.

You’ll also explore creating directories and managing files and directories, including deleting, copying, and renaming them.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Python Software Foundation

Applications to Join the PSF Meetup Pro Network Are Back Open

Following the introduction of the PSF Community Partner Program, the Python Software Foundation (PSF) is pleased to announce that we have reopened the application for Python Meetup groups to join the PSF’s Meetup Pro Network! We’re very excited to bring back this offering to the Python community after applications were temporarily suspended under the broader PSF Grants Program pause last August. Make sure to check out the PSF’s Meetup Pro Network documentation page for more information on how to apply.

Reopening applications for the PSF’s Meetup Pro Network is a small but meaningful step forward for our community support-focused programs. The rest of the PSF Grants Program remains on hold while we work through important considerations, such as what we can responsibly budget and how the program will be structured for long-term sustainability. We look forward to sharing more updates when possible.

The PSF welcomes your comments, feedback, and suggestions regarding the reopening of the PSF Meetup Pro Network on the corresponding Discuss thread. We also invite you to join our upcoming PSF Board or Grants Program Office Hour sessions to talk with the PSF Board and Staff synchronously. If you wish to send your feedback privately, please email grants@python.org.

About the PSF’s Meetup Pro Network

The PSF manages a Meetup Pro account and adds qualified Python-focused Meetup groups to the overarching PSF Meetup Pro Network. Meetup organizers no longer pay for Meetup subscriptions once they become part of the PSF’s network. We currently have 109 groups in the PSF Meetup Pro Network, which costs the PSF $15/month per group.

The PSF can run reports on Meetup activity, such as the number of interested attendees and events. Management of membership and events is left to the group’s organizers. Any registration fees or deposits for RSVPing or paying for registration to an event are also managed solely by the Meetup organizer.

Once a Meetup organizer accepts the invite to join, a notation will be shown under the group name: “Part of Python Software Foundation Meetup Pro Network.” Check out the Meetup Pro overview page for more information.

Criteria and how to apply

We've made the application process and criteria as simple as possible, so Python Meetup groups around the world can easily get the support they need. Along those lines, we’ve kept the requirements short and sweet—to qualify for the PSF’s Meetup Pro Network, a Meetup group must:

- Offer content that is majority Python related

- Include or link to a Code of Conduct in the About section of the Meetup page

- Hold at least 2 events per year (virtual or in-person)

To apply, fill out the short application form on psfmember.org, that asks for basic contact information, as well as gathers information related to the criteria listed above. Make sure you have an account on psfmember.org and that you’re signed in! A PSF Staff member will reach out with any questions or provide the steps needed to add eligible groups to the PSF Meetup Pro Network.

About the Python Software Foundation

The Python Software Foundation is a US non-profit whose mission is to promote, protect, and advance the Python programming language, and to support and facilitate the growth of a diverse and international community of Python programmers. The PSF supports the Python community using corporate sponsorships, grants, and donations. Are you interested in sponsoring or donating to the PSF so we can continue supporting Python and its community? Check out our sponsorship program, donate directly, or contact our team at sponsors@python.org!

March 11, 2026

Python Morsels

Making friendly classes

A friendly class accepts sensible arguments, has a nice string representation, and supports equality checks.

Table of contents

Always make your classes friendly

So you've decided to make a class. How can you make your class more user-friendly?

Friendly classes have these 3 qualities:

- They accept sensible arguments

- Instances have a nice string representation

- Instances can be sensibly compared to one another

- (Optionally) When it makes sense, they embrace dunder methods to overload functionality

An example friendly class

Here's a fairly friendly Point …

Read the full article: https://www.pythonmorsels.com/friendly-classes/

Real Python

Pydantic AI: Build Type-Safe LLM Agents in Python

Pydantic AI is a Python framework for building LLM agents that return validated, structured outputs using Pydantic models. Instead of parsing raw strings from LLMs, you get type-safe objects with automatic validation.

If you’ve used FastAPI or Pydantic before, then you’ll recognize the familiar pattern of defining schemas with type hints and letting the framework handle the type validation for you.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- Pydantic AI uses

BaseModelclasses to define structured outputs that guarantee type safety and automatic validation. - The

@agent.tooldecorator registers Python functions that LLMs can invoke based on user queries and docstrings. - Dependency injection with

deps_typeprovides type-safe runtime context like database connections without using global state. - Validation retries automatically rerun queries when the LLM returns invalid data, which increases reliability but also API costs.

- Google Gemini, OpenAI, and Anthropic models support structured outputs best, while other providers have varying capabilities.

Before you invest time learning Pydantic AI, it helps to understand when it’s the right tool for your project. This decision table highlights common use cases and what to choose in each scenario:

| Use Case | Pydantic AI | If not, look into … |

|---|---|---|

| You need structured, validated outputs from an LLM | ✅ | - |

| You’re building a quick prototype or single-agent app | ✅ | - |

| You already use Pydantic or FastAPI | ✅ | - |

| You need a large ecosystem of pre-built integrations (vector stores, retrievers, and so on) | - | LangChain or LlamaIndex |

| You want fine-grained control over prompts with no framework overhead | - | Direct API calls |

Pydantic AI emphasizes type safety and minimal boilerplate, making it ideal if you value the FastAPI-style development experience.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free sample code you’ll use to work with Pydantic AI and build type-safe LLM agents in Python.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “Pydantic AI: Build Type-Safe LLM Agents in Python” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

Pydantic AI: Build Type-Safe LLM Agents in PythonLearn the trade-offs of using Pydantic AI in production, including validation retries, structured outputs, tool usage, and token costs.

Start Using Pydantic AI to Create Agents

Before you dive into building agents with Pydantic AI and Python, you’ll need to install it and set up an API key for your chosen language model provider. For this tutorial, you’ll use Google Gemini, which offers a free tier perfect for experimentation.

Note: Pydantic AI is LLM-agnostic and supports multiple AI providers. Check the Model Providers documentation page for more details on other providers.

You can install Pydantic AI from the Python Package Index (PyPI) using a package manager like pip. Before running the command below, you should create and activate a virtual environment:

(venv) $ python -m pip install pydantic-ai

This command installs all supported model providers, including Google, Anthropic, and OpenAI. From this point on, you just need to set up your favorite provider’s API key to use their models with Pydantic AI. Note that in most cases, you’d need a paid subscription to get a working API key.

Note: You can also power your Pydantic AI apps with local language models. To do this, you can use Ollama with your favorite local models. In this scenario, you won’t need to set up an API key.

If you prefer a minimal installation with only Google Gemini support, you can install the slim package instead:

(venv) $ python -m pip install "pydantic-ai-slim[google]"

You need a personal Google account to use the Gemini free tier. You’ll also need a Google API key to run the examples in this tutorial, so head over to ai.google.dev to get a free API key.

Once you have the API key, set it as an environment variable:

With the installation complete and your API key configured, you’re ready to create your first agent. The Python professionals on Real Python’s team have technically reviewed and tested all the code examples in this tutorial, so you can work through them knowing they run as shown.

Read the full article at https://realpython.com/pydantic-ai/ »

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Quiz: Threading in Python

In this quiz, you’ll test your understanding of Threading in Python.

By working through this quiz, you’ll revisit how to create and manage threads, use ThreadPoolExecutor, prevent race conditions with locks, and build producer-consumer pipelines with the queue module.

You can also review the written tutorial An Intro to Threading in Python for additional details and code examples.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Quiz: Create and Modify PDF Files in Python

In this quiz, you’ll test your understanding of Creating and Modifying PDF Files in Python.

By working through this quiz, you’ll practice reading, extracting, and modifying PDFs using the pypdf library. You’ll also review how to write new PDFs, concatenate and merge files, crop pages, and encrypt or decrypt documents.

These skills help you automate PDF workflows and handle documents programmatically in Python.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

March 10, 2026

PyCoder’s Weekly

Issue #725: Generators, __init__.py, Pointblank, and More (March 10, 2026)

#725 – MARCH 10, 2026

View in Browser »

Invent Your Own Comprehensions in Python

Python doesn’t have tuple, frozenset, or Counter comprehensions, but you can invent your own by passing a generator expression to any iterable-accepting callable.

TREY HUNNER

What Does Python’s __init__.py Do?

Learn how Python’s __init__.py declares packages, initializes variables, simplifies imports, and controls what gets exported.

REAL PYTHON course

Replay: Where Developers Build Reliable AI

Replay is a practical conference for developers building real systems. The Python AI & versioning workshop covers durable AI agents, safe workflow evolution, and production-ready deployment techniques. Use code PYCODER75 for 75% off your ticket →

TEMPORAL sponsor

Validating Data With Pointblank in Python

Bad data results in bad choices. This article introduces you to Pointblank a data verification library.

MARK PITBLADO

Python Jobs

Python + AI Content Specialist (Anywhere)

Articles & Tutorials

Guido Interviews Thomas Wouters

After last year’s release of the Python documentary, Guido decided to explore those contributors who weren’t mentioned. He’s started a written interview series with a variety of contributors over Python’s first 25 years. This interview is with Thomas Wouters.

GUIDO VAN ROSSUM

Using tox to Test Across Multiple Django Versions

tox is a popular testing tool that uses isolated virtual environments to put your code through its paces using different versions of Python. This post shows you how to use it to test your Django App across multiple versions of Django.

DJANGOTRICKS

What asyncio Primitives Get Wrong About Shared State

Aaron’s company tried Event, Condition, and Queue for handling concurrent shared state, but each one still breaks under real concurrency. This article is about the observable pattern that finally worked for them.

AARON HARPER

Deprecate Confusing APIs Like os.path.commonprefix()

In this opinion piece, Seth argues that os.path.commonprefix() is confusing due to its placement in the os.path module, and this results in security issues. He thinks it should be deprecated, read on to learn why.

SETH LARSON

Replacing tox With uv

UV is quickly becoming the only tool you need in Python, this article looks at how UV can be used to test different versions of dependencies replacing what is traditionally done with tox.

CHANGS.CO.UK • Shared by Jamie Chang

A History of Attempts to Eliminate Programmers

From COBOL in the 1960s to AI in the 2020s, every generation promises to eliminate programmers. Explore the recurring cycles of software simplification hype.

IVAN TURKOVIC

Building Rapidlog: Why I Made a 3x Faster Python Logger

Siddharth built a benchmark-focused Python logging implementation for high-concurrency workloads. This article tells you why and how it was done.

DEV.TO • Shared by Siddharth Pogul

How to Use the OpenRouter API to Access Multiple AI Models

Access models from popular AI providers in Python through OpenRouter’s unified API with smart routing, fallbacks, and cost controls.

REAL PYTHON

Automate Python Data Analysis With YData Profiling

Automate exploratory data analysis by transforming DataFrames into interactive reports with one command from YData Profiling.

REAL PYTHON

Projects & Code

Events

Python asyncio Internals

March 10, 2026

LUMA.COM • Shared by Adarsh Divakaran

Weekly Real Python Office Hours Q&A (Virtual)

March 11, 2026

REALPYTHON.COM

Python Atlanta

March 12 to March 13, 2026

MEETUP.COM

PyConf Hyderabad 2026

March 14 to March 16, 2026

PYCONFHYD.ORG

DFW Pythoneers 2nd Saturday Teaching Meeting

March 14, 2026

MEETUP.COM

DjangoCologne

March 17, 2026

MEETUP.COM

PyCascades 2026

March 21 to March 23, 2026

PYCASCADES.COM

PythonAsia 2026

March 21 to March 24, 2026

PYTHONASIA.ORG

Happy Pythoning!

This was PyCoder’s Weekly Issue #725.

View in Browser »

[ Subscribe to 🐍 PyCoder’s Weekly 💌 – Get the best Python news, articles, and tutorials delivered to your inbox once a week >> Click here to learn more ]

Real Python

Working With APIs in Python: Reading Public Data

Python is an excellent choice for working with Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), allowing you to efficiently consume and interact with them. By using the Requests library, you can easily fetch data from APIs that communicate using HTTP, such as REST, SOAP, or GraphQL APIs. This video course covers the essentials of consuming REST APIs with Python, including authentication and handling responses.

By the end of this video course, you’ll understand that:

- An API is an interface that allows different systems to communicate, typically through requests and responses.

- Python is a versatile language for consuming APIs, offering libraries like Requests to simplify the process.

- REST and GraphQL are two common types of APIs, with REST being more widely used for public APIs.

- To handle API authentication in Python, you can use API keys or more complex methods like OAuth to access protected resources.

Knowing how to consume an API is one of those magical skills that, once mastered, will crack open a whole new world of possibilities, and consuming APIs using Python is a great way to learn such a skill.

By the end of this video course, you’ll be able to use Python to consume most of the APIs that you come across. If you’re a developer, then knowing how to consume APIs with Python will empower you to integrate data from various online sources into your applications.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Luke Plant

Announcing fluent-codegen

This post announces fluent-codegen, a Python library for generating Python code. Not everyone needs this, but when you need it, you’ll probably know, and you’ll want probably want a decent solution that is not based on string concatenation.

The history of this project is that it started out as a codegen module in fluent-compiler, which is an implementation of Project Fluent, Mozilla’s internationalisation solution. So the word “fluent” referred to that originally, but now it refers to a set of nice APIs for building up Python expressions.

As I needed a code generation library for another purpose, I pulled out this library and fleshed it out into a relatively complete, standalone project. It has also evolved quite a bit since its earlier form, and is a pretty well rounded library now. You can check out the nice docs, which include a nice little toy example of a “SVG to Python Turtle” compiler. Enjoy!

Real Python

Quiz: Python Descriptors: An Introduction

In this quiz, you’ll test your understanding of Python Descriptors.

By working through this quiz, you’ll revisit the descriptor protocol, how .__get__() and .__set__() control attribute access, and how to implement read only descriptors. You’ll also explore data vs. non-data descriptors, attribute lookup order, and the .__set_name__() method.

These exercises help you reason about real descriptor behavior and see when and why to use them in your code.

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]

Wingware

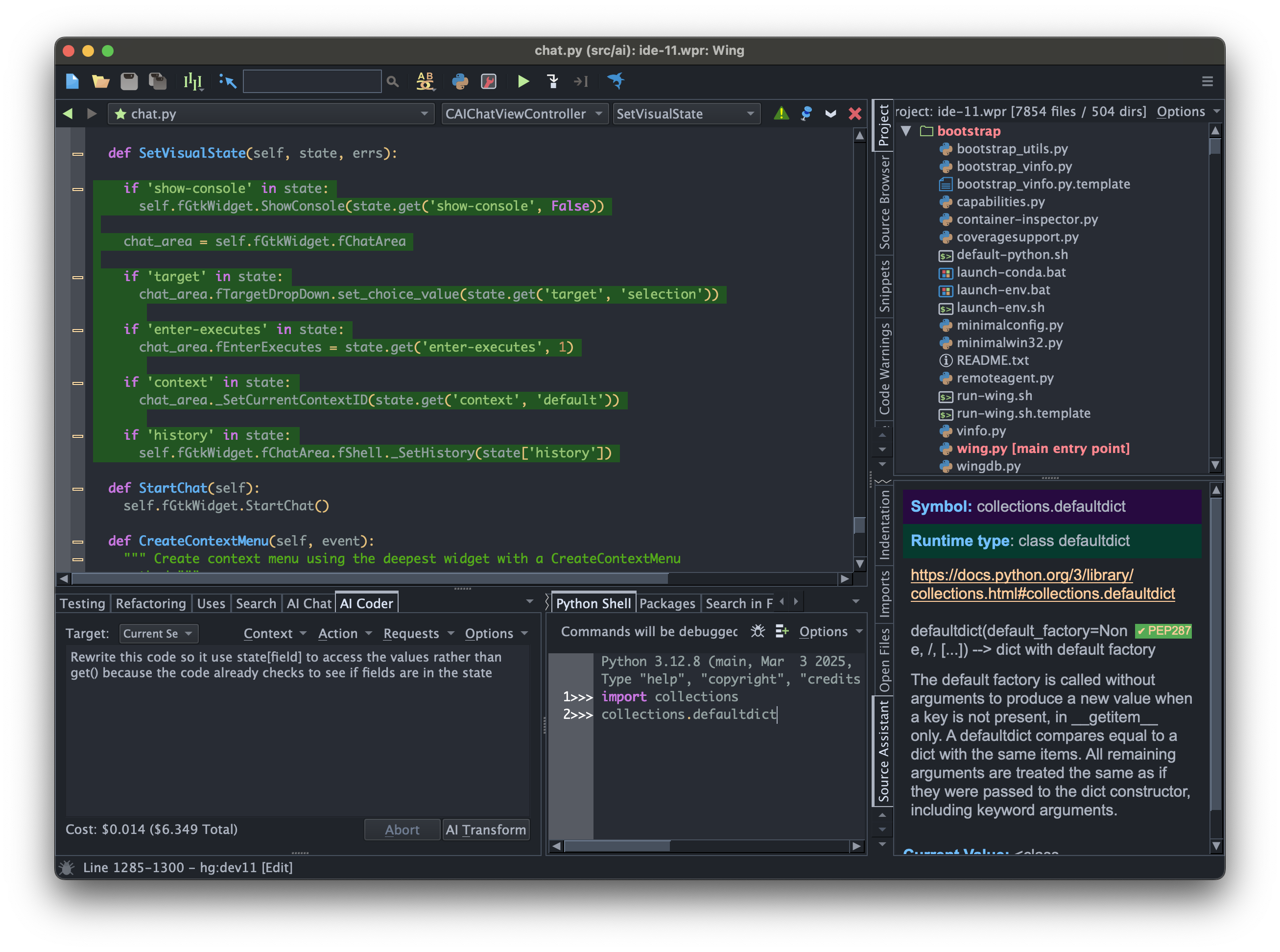

Wing Python IDE Version 11.1 - March 10, 2026

Wing Python IDE version 11.1 has been released with improved pseudo TTY emulation in OS Commands, Start Terminal on Windows, syntax highlighting for Rust and TOML, support for newer OpenAI models in AI Chat, new Stop on SystemExit debugger preference, and other minor features and bug fixes.

Downloads

Wing 10 and earlier versions are not affected by installation of Wing 11 and may be installed and used independently. However, project files for Wing 10 and earlier are converted when opened by Wing 11 and should be saved under a new name, since Wing 11 projects cannot be opened by older versions of Wing.

New in Wing 11

New in Wing 11

Improved AI Assisted Development

Wing 11 improves the user interface for AI assisted development by introducing two separate tools AI Coder and AI Chat. AI Coder can be used to write, redesign, or extend code in the current editor. AI Chat can be used to ask about code or iterate in creating a design or new code without directly modifying the code in an editor.

Wing 11's AI assisted development features now support not just OpenAI but also Claude, Grok, Gemini, Perplexity, Mistral, Deepseek, and any other OpenAI completions API compatible AI provider.

This release also improves setting up AI request context, so that both automatically and manually selected and described context items may be paired with an AI request. AI request contexts can now be stored, optionally so they are shared by all projects, and may be used independently with different AI features.

AI requests can now also be stored in the current project or shared with all projects, and Wing comes preconfigured with a set of commonly used requests. In addition to changing code in the current editor, stored requests may create a new untitled file or run instead in AI Chat. Wing 11 also introduces options for changing code within an editor, including replacing code, commenting out code, or starting a diff/merge session to either accept or reject changes.

Wing 11 also supports using AI to generate commit messages based on the changes being committed to a revision control system.

You can now also configure multiple AI providers for easier access to different models.

For details see AI Assisted Development under Wing Manual in Wing 11's Help menu.

Package Management with uv

Wing Pro 11 adds support for the uv package manager in the New Project dialog and the Packages tool.

For details see Project Manager > Creating Projects > Creating Python Environments and Package Manager > Package Management with uv under Wing Manual in Wing 11's Help menu.

Improved Python Code Analysis

Wing 11 makes substantial improvements to Python code analysis, with better support for literals such as dicts and sets, parametrized type aliases, typing.Self, type of variables on the def or class line that declares them, generic classes with [...], __all__ in *.pyi files, subscripts in typing.Type and similar, type aliases, type hints in strings, type[...] and tuple[...], @functools.cached_property, base classes found also in .pyi files, and typing.Literal[...].

Updated Localizations

Wing 11 updates the German, French, and Russian localizations, and introduces a new experimental AI-generated Spanish localization. The Spanish localization and the new AI-generated strings in the French and Russian localizations may be accessed with the new User Interface > Include AI Translated Strings preference.

Improved diff/merge

Wing Pro 11 adds floating buttons directly between the editors to make navigating differences and merging easier, allows undoing previously merged changes, and does a better job managing scratch buffers, scroll locking, and sizing of merged ranges.

For details see Difference and Merge under Wing Manual in Wing 11's Help menu.

Other Minor Features and Improvements

Wing 11 also adds support for Python 3.14, improves the custom key binding assignment user interface, adds a Files > Auto-Save Files When Wing Loses Focus preference, warns immediately when opening a project with an invalid Python Executable configuration, allows clearing recent menus, expands the set of available special environment variables for project configuration, and makes a number of other bug fixes and usability improvements.

Changes and Incompatibilities

Since Wing 11 replaced the AI tool with AI Coder and AI Chat, and AI configuration is completely different than in Wing 10, you will need to reconfigure your AI integration manually in Wing 11. This is done with Manage AI Providers in the AI menu. After adding the first provider configuration, Wing will set that provider as the default. You can switch between providers with Switch to Provider in the AI menu.

If you have questions, please don't hesitate to contact us at support@wingware.com.

March 09, 2026

The Python Coding Stack

Field Notes: First, Second, and Five Hundred and Twenty-Third • [Club]

Most of my posts on The Python Coding Stack, whether in the main publication or here in The Club, typically focus on some aspect of core Python and explore it through a step-by-step approach, a mini-project, or sometimes through an essay-type article.

But today, I’ll write a short post about some tools I came across that may be interesting. I’ll keep the post short since, if you’re interested, you can easily explore the packages independently – you won’t need my explanatory efforts.

Remember some of the earliest code you ever wrote? It may have looked like this:

first = input(”Enter the first number: “)

second = input(”Enter the second number: “)

print(

f”The sum of the two numbers is {float(first) + float(second)}”

)Those days are long gone. But what if you wanted this code to work for any number of inputs, not just two?

I’m not talking about the code to work out the sum itself. You’d probably use a list to collect all the numbers and the sum() built-in function, or just use a running total. Whatever.

The annoying part is making user-friendly strings when asking for the input – it’s fine to write "first" and "second" when there are only two prompts – and then when showing the result, which currently says "two numbers". But what if you have more?

I came across this need several times, but my solution has always been to change the string so that it’s general enough to work in all cases. I’m lazy, I know.

In any case, recently I decided to look for solutions. And of course, they exist! Everything seems to exist in the Python ecosystem. Several solutions…

num2words

The first solution is probably the simplest: the num2words package doesn’t do much beyond converting numbers to words, as its name suggests. You’ll need to install num2words using pip, uv, or whatever you use to install packages.

>>> import num2words

>>> num2words.num2words(34)

‘thirty-four’The main function in the num2words module is also called num2words(), as often happens with such modules!

How far can it go?

>>> num2words.num2words(5468.23)

‘five thousand, four hundred and sixty-eight point two three’Working in Spanish?

>>> num2words.num2words(5468.23, lang=”es”)

‘cinco mil cuatrocientos sesenta y ocho punto dos tres’Or Japanese?

>>> num2words.num2words(5468.23, lang=”ja”)

‘五千四百六十八点二三’Real Python

Python Gains frozendict and Other Python News for March 2026

After years of community requests, Python is finally getting frozendict. The Steering Council accepted PEP 814 in February, bringing an immutable, hashable dictionary as a built-in type in Python 3.15. It’s one of those additions that feels overdue, and the frozenset-to-set analogy makes it immediately intuitive. This is just one piece of a busy month of Python news.

Beyond that, February brought security patches, AI SDK updates, and some satisfying infrastructure improvements under Python’s hood. Time to dive into the biggest Python news from the past month!

Join Now: Click here to join the Real Python Newsletter and you’ll never miss another Python tutorial, course, or news update.

Python Releases and PEP Highlights

The Steering Council was active in February, with several PEP decisions landing. On the release side, both the 3.14 and 3.13 branches got maintenance updates.

Python 3.15.0 Alpha 6: Comprehension Unpacking and More

Python 3.15.0a6 shipped on February 11, continuing the alpha series toward the May 5 beta freeze. This release includes several accepted PEPs that are now testable:

- PEP 798: Unpacking in comprehensions using

*and** - PEP 799: A high-frequency, low-overhead statistical sampling profiler

- PEP 686: UTF-8 as the default text encoding

- PEP 728:

TypedDictwith typed extra items

PEP 798 is the kind of quality-of-life improvement that makes you smile. It lets you flatten or merge collections directly in a comprehension:

>>> lists = [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5]]

>>> [*it for it in lists]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> dicts = [{"a": 1}, {"b": 2}]

>>> {**d for d in dicts}

{'a': 1, 'b': 2}

No more writing explicit loops just to concatenate a list of lists.

The JIT compiler continues to show gains: 3-4% on x86-64 Linux over the standard interpreter and 7-8% on AArch64 macOS over the tail-calling interpreter, matching the numbers from alpha 5.

Note: Alpha 7 is scheduled for March 10, 2026, with the beta phase starting May 5. If you maintain packages, now is a great time to test against early builds.

Python 3.14.3 and 3.13.12: Maintenance Releases

On February 3, the team shipped Python 3.14.3 with around 300 bug fixes and Python 3.13.12 with about 240 fixes. No new features here, but if you’re running either version in production, it’s worth grabbing these patches to stay current.

PEP 814 Accepted: frozendict Joins the Built-Ins

This one has been on many Python developers’ wishlists for over a decade. PEP 814, authored by Victor Stinner and Donghee Na, adds frozendict as a built-in immutable dictionary type in Python 3.15.

The concept is straightforward. Just as frozenset gives you an immutable version of set, frozendict gives you an immutable version of dict:

>>> config = frozendict(host="localhost", port=8080)

>>> config["host"]

'localhost'

>>> config["host"] = "0.0.0.0"

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

TypeError: 'frozendict' object does not support item assignment

Read the full article at https://realpython.com/python-news-march-2026/ »

[ Improve Your Python With 🐍 Python Tricks 💌 – Get a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. >> Click here to learn more and see examples ]